A RESPECTFUL REMEMBERANCE

By Hugh Lovelady

In the days when Las Vegas hotel marquees were ablaze with the biggest names in show business, it’s often hard to reconcile in your mind what you saw then and what you see now. It all seems so hazy now; like a dream you remember: waking up and hoping what you dreamt about was true, that there was indeed a time when over 1,500 musicians were making their living playing in the Entertainment Capitol of the World. In the 50’s 60’s 70’s and up until 1989 there was plenty of work for musicians, both in the big, often 30 piece house orchestras, as well 15 piece bands in the lounges. In those years, house band musicians were well aware of the big name musical acts as well as the people who conducted for them. Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis, Jr. and their conductors often commanded the most musical respect from musicians. However, there was one conductor who seemed to be as respected, if not more respected than all the rest. The musicians who played under his leadership universally liked him. He had the reputation of treating the musicians with respect, dignity, and courtesy, mixed with the obvious display of his own humility. When he rehearsed the house band, musicians sat up a little straighter, listened more intently, and each in their own way dialed up their A game. During a rehearsal, he was known to have “satellite dish” ears, detecting wrong notes, wrong chords or out of tune notes instantly, all the while correcting the offending musician with courtesy but making it very clear it was the music and the performance of the music that was most important. Just as important, all musicians knew he wasn’t conducting someone else’s arrangements or music for just an act…he was conducting his arrangements, his music and he knew exactly how he wanted it to sound. I remember quite vividly the first time I saw his name. I was between shows, resting up from having room keys thrown on stage, often zinging by my own head or a fellow musician’s head, as well as spending my time between tunes counting the pairs of women’s underwear that had been thrown on stage. I had been playing “Suspicious Minds” and “In the Ghetto” with Elvis Presley at the Las Vegas Hilton. The lead alto player from the MGM hotel, a good friend and mentor, asked me to join him in the MGM coffee shop between shows. I parked at the Flamingo Hotel (in those days, the original hotel that Bugsy Siegel built) and walked out into the night on the famed Las Vegas Strip, casually turning my head to the right and noticing the Sands Hotel marquee. I noticed in big letters that Lena Horne was appearing there and under her name, in equally big letters: CONDUCTED BY ROBERT M. FREEDMAN.

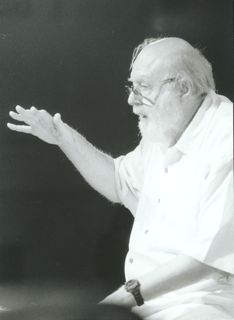

On 23 December of 2018, the President of Musicians Local 586, Jerry Donato, informed me that Bob Freedman had passed away. I knew Bob was in poor health from visiting him. I had already noticed his emails to me were now shorter, often just one or two worded comments. His quick wit was now tempered and restrained and his often sarcastic, humorous and wry observations about the music business, both locally and nationally, were gone. It was obvious the phone call placed to me by Jerry was painful to make, as it was as painful for me to hear. Two months passed and Jerry asked me to write a personal, final remembrance for Bob Freedman. I agreed to do so, knowing full well anything I attempted to write would fall short in describing the totality of his musical accomplishments as well as the impact of the man on the people and musicians around him. That being said, I am attempting to honor Jerry’s request: to honor the man we were both lucky enough to know and call a friend.

In my own line of musical work, I’ve been lucky: at the right place at the right time, which has given me the unique opportunity to have known and worked with several musicians that have been able to tell me what it was really like, “in the day.” “The way it was” so to speak. One of those musicians, a living, breathing time portal to the past, was Bob Freedman.

It would be good, at this point, to inform many of the Phoenix musicians who might not have known Bob, the musical resume he left behind. This is only a very small part of his work. To cover it all, would take the next six editions of The Pitch from cover to cover. He excelled at every facet of his craft, leaving an indelible imprint to all who knew him. Here are but a few of his musical accomplishments:

1. Grammy Award winner (shared with Quincy Jones), for Overture Part 1 from the WIZ motion picture sound track album. He was subsequently nominated for three additional Grammy wards.

2. He arranged for: Harry Belafonte, Arthur Blythe, Ron Carter, Maynard Ferguson, Marvin Hamlisch, Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Billy Joel, Herbie Mann, Wynton Marsalis, Carly Simon, Sarah Vaughn, Grover Washington Junior, and Joe Williams

3. Musical Director and Conductor for Lena Horn, Harry Belafonte. Director/Pianist for the Merv Griffin Show. Co-orchestrator (with Al Cohn) of the Broadway musical RAISIN which won the Tony Award for Best Musical and the Grammy award for Best Original Cast Album

4. CD recording: A tribute to Artie Shaw, written for Boston based clarinetist

Dick Johnson. CD recordings: The World of Ron Carter and Ron Carter’s Great New York Big Band. CD recording for Wynton Marsalis: “Hot House Flowers.”

4. Film arranger and on screen conductor for the film: One Trick Pony with Paul Simon. Co-arranger and on-screen conductor for The China Syndrome, The Love of Ivey and The Seduction of Joe Tynan.

5. As a Performer: Baritone Saxophone with Woody Herman, Tenor saxophone and clarinet with Duke Ellington, Alto saxophone with the Herb Pomeroy Big Band in Boston, Mass. Played piano with Serge Chaloff and the Vido Musso quartets. Played piano for Miles Davis on Miles’ CD “Miles Davis at the Hi-Hat” in Boston.

6. Educator: Faculty member at BERKLEE COLLEGE OF MUSIC, September 1982 through June 1985. Chairman of the Arranging Department at Berklee College of Music, June 1985 through August 1992.

7. Staff arranger and orchestrator for the CBS, NBC and ABC television networks in New York City.

When Bob “retired” he moved to Gilbert and as fate would have it, less than two miles from my house. Much of the work he had written for “in the day”

had now evaporated. The great “saloon” singers were gone, as well as the orchestras that once accompanied them. Network television was nothing even close to the great live television shows of the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. The musicians employed as “staff musicians” in the television studios were let go in the late 60’s and early 70’s, the major studios only wanting to hire if needed. He received commissions from time to time, especially from Europe and one huge commission which all his friends, nationally and locally, were absolutely thrilled about: He was asked to write the music for Ron Carter’s New York Big Band. The musical result was an absolutely swinging affair played by some of New York’s finest musicians, playing the music of one of the country’s finest arrangers. Characteristically, when the recording was finished, he gave away most of the arrangements to local rehearsal bands.

Bob settled into daily life in Gilbert and began doing locally what he had already done on the world stage: write music.

Bob wrote two great pieces for Young Sounds of Arizona. He wrote and arranged several dazzling pieces for Christina Steffen’s wonderful Desert Echoes Flute Project. Several local musicians began tinkering with the idea of making their own CD. Jerry Donato recorded “It’s a Cool Heat” bringing in one of Los Angeles’ finest pianists, Pete Jolly, with Bob writing all the arrangements and conducting. Joe Corral, Phoenix’s finest jazz flute player, recorded his album, “Groovin Higher,” with arrangements and musicians second to none. Local singer, Monte Procopio, hired Bob to write arrangements for a big band. Monte paid for the recording time, the musicians and the arrangements out of his own pocket. The band put together for that recording session maybe the finest big band ever assembled in Phoenix. Bob rehearsed the Procopio band with the same efficiency, professionalism and pursuit of excellence that he was known for in Las Vegas and around the world so many years before. Local singer Jenny Jarnigan also employed Bob and many musicians for several wonderful sessions.

Bob didn’t drive in those days. Since I lived so close, it was my job to get him to these recording sessions or the rehearsals for them. In all my life, I have never enjoyed a car ride so much. Bob talked of the heyday of the New York recording studios. He wrote music for television shows or jingles and worked with world-class musicians like Stanley Drucker, the principal clarinetist of the NY Phil as well as Julius Baker, principal flutist and David Nadien The NY Phil’s concertmaster. Jazz musicians were doing much of the lucrative New York session work in those days. Bob worked with saxophone sections that contained Phil Woods, Zoot Sims, Jerry Dodgion. Trumpet sections with a young Doc Severinson, Clark Terry, Johnny Frosk and Thad Jones. Studio trombone sections contained the likes of Kai Winding, J.J. Johnson and Urbie Green. Bob informed me, in those days, there was so much work, session musicians often kept duel sets of instruments at different studios so they could walk in, blow a few notes and get ready for the next recording He also worked with the greatest woodwind doublers of the day: George Marge, Phil Bodner, Romeo Penque and Ray Beckenstein.

During those car rides, I learned what it was like to sit in a saxophone section with Johnny Hodges and have him yell at you because you didn’t get the music up fast enough. It didn’t matter Duke had 6 full books and the entire band had all the music memorized. I learned of the kindness of Billy Strayhorn and the aloofness of Duke Ellington. Bob was in the army with Chet Baker. He talked of Chet’s tortured life and what may have led to his tragic death. I learned, uncharacteristically, Miles Davis was nice and complimentary to him on a Boston recording session where Bob played piano. I began to look forward to the car rides as much or more than the actual recording sessions themselves. I also began to realize Bob wasn’t name-dropping. Like myself, he was looking back in that time portal in awe as an admirer. It didn’t seem to occur to him he deserved to be admired and respected as much as anyone else he was telling me about. Great humility: often the hallmark of the greatest of the great.

Whether rehearsing a local rehearsal band, a band for a recording session or the house orchestra at Caesar’s Palace, I can’t recall anyone who was as skillful at rehearsing a band as well as Bob Freedman. I don’t know if he had a certain method of going about the rehearsal or just rehearsed as problems presented themselves. I know the musicians gave him instantaneous respect and truly wanted to play well for him. Perhaps Bob’s own knowledge of the music coupled with a musician’s desire to play to their best ability brought about the sought after results. Most any tune, within 20 minutes of rehearsing, was ready to perform.

In his last years there seemed to be a pervasive sadness about him. He well knew what we all know: “All gigs end.” The gig may last two days, two weeks or twenty years but in the end, they never last forever. He jokingly once told me “every musician he ever knew was depressed.” I suspect he already knew what I was learning: looking back could be painful. I also suspect that by looking back it helped him cope with the present musical landscape of today: that looking back perhaps gave him a soothing comfort with what must have looked like, to him at least, the dark, empty musical abyss of the musical climate of today.

Hopefully, all musicians will come in contact with their own version of a Bob Freedman. Perhaps it will be a great teacher or player who inspired you to work harder and help you achieve the goals you seek. For Jerry Donato and myself, knowing the real Bob Freedman was perhaps one of the greatest experiences of our musical lifetime.

I receive emails everyday simply titled, “Daily Inspirations. They are small tidbits designed to help one understand and deal with the rigors of daily life. Below is the one I received three days after I learned of Bob’s passing. Aside from all the great music, I choose to remember him in this way.

“The person who is a master in the art of living makes little distinction between their work and their play, their labor and their leisure, their mind and their body, their education and their recreation, their love and their religion. They hardly know which is which. They simply pursue their vision of excellence and grace in whatever they do, leaving others to decide whether they are working or playing. To them, they are always doing both. “

Categories: News